On Wednesday, Oct. 11, Ramona Kitto Stately gave a lecture in Viking Theater on the violence perpetrated against Minnesota’s indigenous communities. Titled “Seeing Minnesota’s Indigenous Histories,” her lecture focused on forgotten stories of oppression against the Dakota people after the U.S.-Dakota War and how that persecution affected the surviving families and future generations.

Stately has special reason to be incensed over Minnesota’s treatment of the Dakota people. Not only is she a member of the Santee-Sioux Dakota Nation that lived in Minnesota for over 12,000 years, but her great-great-grandfather was also sentenced to death after the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. While he survived due to a commutation of his sentence, the violence wrought against the Dakota people has a certain raw proximity for Stately.

After introducing herself and her Dakota background, Stately gave an overview of certain aspects of Dakota language and culture relevant to the government’s transgressions. Stately’s great-grandfather was born at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers, known in the Dakota language as Bdote. Bdote and the Minnesota River Valley hold special significance for the Dakota people, who lived there for thousands of years and would bury their dead in the bluffs of the Mississippi. The site also holds immense spiritual significance: the Dakota believe it is the place where they were created, and refer to it as “the center of our universe.”

The U.S. army built Fort Snelling next to Bdote in order to protect encroaching settlers from Native-American raids. Despite the theft of Dakota lands and the spiritual significance of Bdote, little mention of either is given at the current, Minnesota Historical Society-run Fort Snelling.

“You can go on an education trip, you can have your birthday here,” Stately said. “You can have tea with Mrs. Snelling. And that invisible story remains.”

Furthermore, according to Stately, the Fort was part of a larger pattern of provocation and punishment.

“The idea is, first you build a fort, you create relationships, you make a treaty, then you create something to cause a disturbance and then you can imprison the men,” Stately said.

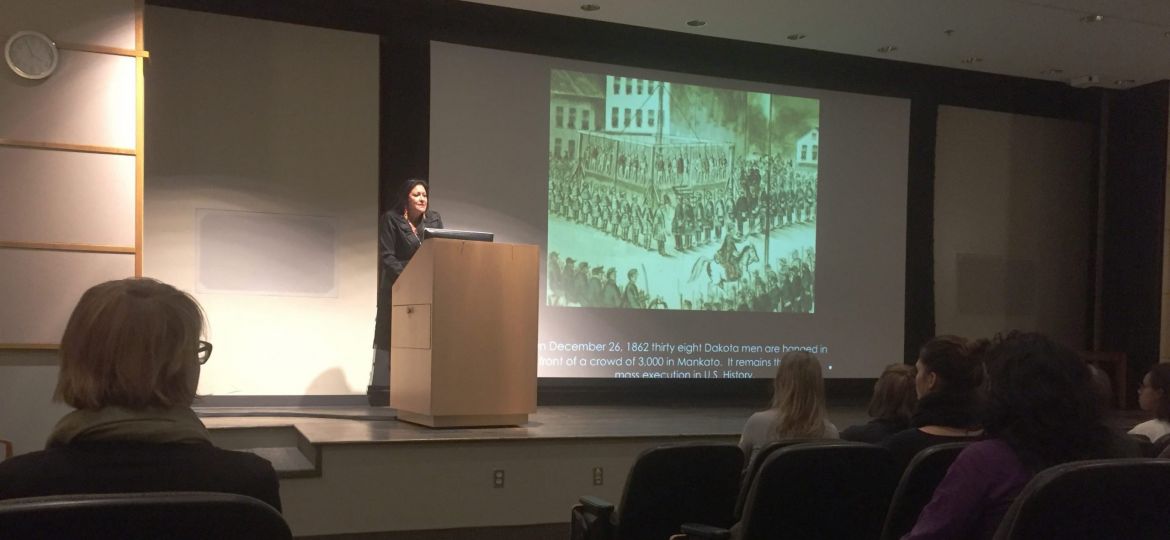

Indeed, that sequence of events played out in the U.S.-Dakota War. After the six week conflict, 300 Dakota men were sentenced to death, though President Lincoln commuted the sentences of all but 38. On Dec. 26, 1862, a crowd of 3,000 in Mankato witnessed the public hanging of those 38 Dakota men, the largest mass execution in American history.

“The Minnesota State Fair brought in about 500 people its first year. You can see what the pulse was of the community here.”

The Minnesota government’s ire towards the Dakota people extended far beyond the imprisoned men.

“Governor Ramsey, governor of the state of Minnesota, said that ‘the Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of this state,” Stately said.

The Dakota women and children were thereafter rounded up and forced to march 150 miles across the state to be shipped downriver, a six day forced march through frigid November weather. Beyond the toll of the march itself, the women and children were led through all the settler towns that suffered from Dakota attacks, just as the settlers were burying their dead.

“Every one of these battle towns that our Dakota women and children and elders and elder men walked through, they were attacked, violently,” Stately said. “In the span of six days, hundreds were dead and just thrown off to the side of the road.”

The Dakota women and children who survived were slated to be shipped out of the state down the Mississippi River. However, the water was frozen, and the Dakota were instead interned on Pike Island by Fort Snelling until the waters became navigable. Not only was the site by Fort Snelling, but it was at Bdote. The Dakota’s lodgings were woefully inadequate for the Minnesota winter and an average of four people died each day.

According to Stately, only now is Minnesota beginning to reckon with its history and make amends.

“At Bdote, our genesis became a place of genocide,” Stately said. “But down below, you can walk down into the river valley, and see a monument, a memorial to Dakota women … There’s a fee to pay at the front, but if you go to pray, and you’re Native, you don’t pay the fee. So it’s very different, there have been prayers there, we can have ceremony there, we don’t have to pull a permit.”

Just this year, the Minnesota Historical Society published a book labeling the treatment of the Dakota a genocide for the first time and the internment at Pike Island a concentration camp.

Every other year since 2002, Stately and other Dakota women have walked the 150 mile trail first tread by the Dakota women and children in 1862. As they walk, they plant prayer flags and pray for the Dakota women that first walked that path. They also pass through the ‘battle-towns’ where the captive Dakota were originally attacked by furious settlers. The first few years were tumultuous, with some residents throwing rocks and hurling racial slurs at the women. However, relations between the towns and the marchers have gradually improved. Stately views the walk and engagement with the towns as part of a much needed healing process.

“This is the way of creating healing, because we can’t hold it in, otherwise we continue the trauma to the next generation,” Stately said.

Stately concluded her talk by emphasizing the economic vitality casinos and other Indigenous businesses have brought to Minnesota, and how these developments remain largely invisible to many.

“If we talked about this in the classroom for Native kids, how proud would they be? Wow, there’s 11 reservations in the state of Minnesota, 13 casinos, every single one of them is the largest employer in their county.”