A study in 2014 found that two-thirds of female chronic pain patients thought that their symptoms were taken less seriously because they were women.

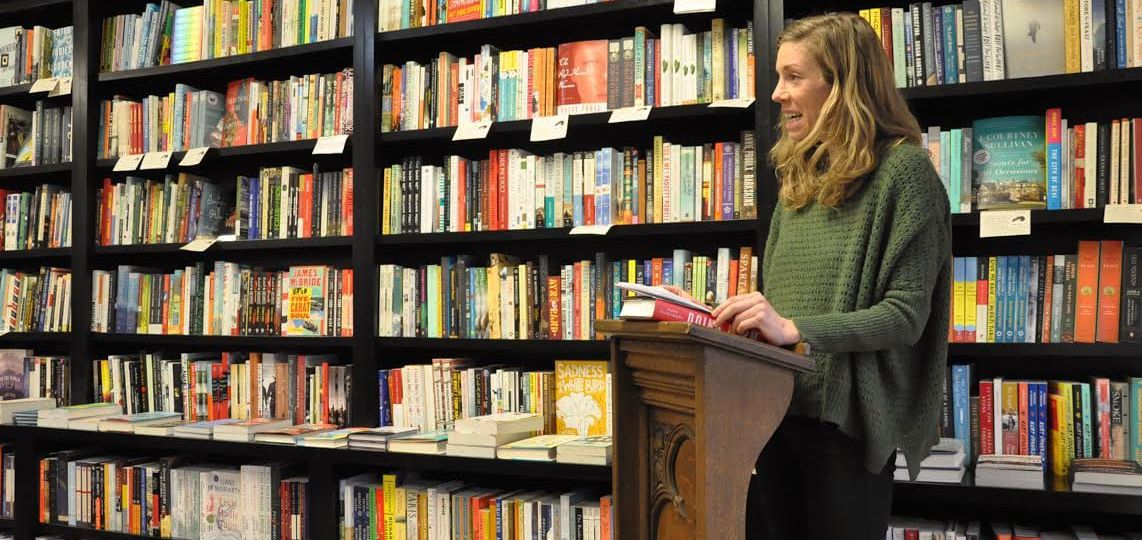

That was one of the many shocking facts from Maya Dusenbery’s book talk on March 14. Dusenbery, Editorial Director of trailblazing site feministing.com and alumni of Carleton College, returned to Northfield to talk about her new book, “Doing Harm.” The book explores how gender bias plays out in medical care in the United States.

When Dusenbery developed Rheumatoid Arthritis, she was inspired to hear other stories of women with similar diseases. According to the author, “Chronic pain affects 100 million people in the United States, making it the biggest health problem we face nationally.”

However, while Dusenbery was diagnosed within six months, female autoimmune patients often go undiagnosed for years.

Dusenbery talks about what she calls the ‘trust gap.’ She heard stories where women felt like their symptoms were minimized or disbelieved entirely. Rather than view these women as reliable reporters of their own pain, doctors attributed their symptoms to stress or depression. Even worse, doctors dismissed these women’s pain diagnoses as being all in their heads.

“I’m not crazy like the doctors tell me” is one of the first things Dusenbery frequently hears from the female patients she talks to. Dusenbery attributes this reasoning partly to the societally ingrained notions about hysteria and women. Hysteria, a mental disorder characterized by emotional excitability or a panicked state, is stereotypically attributed to women. Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud said that hysteria was an exclusively female disease. And, while hysteria is no longer recognized by medical authorities as a medical disorder, the social implications still last.

One patient, as mentioned in “Doing Harm,” spent thirteen years telling doctors about the pain she experienced before they actually diagnosed her. During this time, people called her names like “malingerer,” “liar” and “hysterical.”

“Women have to prove that we are really in pain,” the patient told Dusenbery, as recorded in “Doing Harm.” When it comes to diagnosing symptoms not found on x-rays and scanners, women are not seen as reliable reporters. To make matters worse, they have to go lengths to prove their pain is not in their heads.

They walk the tightrope when recording their pain to doctors. If these women cry, they are seen as hysterical, but if they appear too stoic, a characteristic attributed to males, they must not have real pain. A stoic woman doesn’t fit conventional gender norms, yet a woman who falls to pieces seems like a malingerer who is inventing her symptoms. These women have to be assertive enough to be taken seriously but not too assertive lest they risk appearing like they are too dominant or overbearing. Even in appearance, they must play the part.

“Healthcare providers have a strong ‘beautiful is healthy’ bias especially when it comes to women,” Dusenbery said. In another study Dusenbery mentioned, patients who were judged as attractive by their doctors were recorded to experience less pain. These women combatted this beauty bias by not wearing makeup to their appointments or adjusting how they dressed to avoid comments like, ‘You always look so healthy,’ from their doctors. Even with these adjustments, many women still found that doctors didn’t believe them unless they brought a male with them to their appointments to verify their reports. Sadly, there exists a general tendency to not treat female voices with the same authority of male voices.

When Dusenbery interviewed men whose pain went years undiagnosed, she found the same frustration she found in women. But when she asked if doctors questioned their mental health, their sanity or called them liars, they said, “No, I can’t really relate to that.”

Dusenbery hopes her book “Doing Harm” can shed some light on the gender bias within the medical field and help women realize that they are not alone in their experiences. When it comes to these female patients’ experiences, Dusenbery wants them to know that it is not all in their heads.

favaro1@stolaf.edu